Sadhana: an ancient perspective on the art of practice

by Jim Kulackoski

My first love was music. As a child, I learned the cello, which exposed me to the vast and rich world of classical music. I spent many hours practicing and grew to love music more and more. In college, I decided to pursue a career in music performance, and the intensity of my practice increased. Long, intense hours of study and practice, with little rest in between, left me feeling tired and sore, rather than with a sense of accomplishment.

Eventually I became frustrated and disillusioned. The very love and enthusiasm I originally had for the cello and for music started to wane. While I had the drive and talent to be successful, I did not then understand how to practice effectively. What I wished I had known earlier was what I learned in my study of yoga philosophy, the concept of sādhanā.

Sādhanā is a Sanskrit word meaning “the means by which something is accomplished.” It is a way of practicing in which an art or skill is perfected to a state of mastery. Sādhanā is not only the act of practice, but also with a particular emphasis on how to practice.

Whether the goal is mastering a cello concerto or self-realization through yoga, practice is necessary for success. As the old saying goes, “practice makes perfect.” But what makes perfect practice is often a mystery.

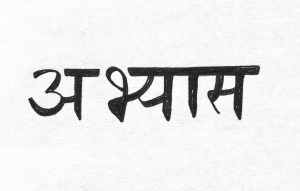

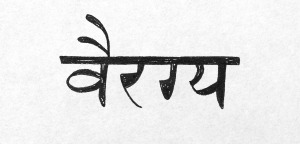

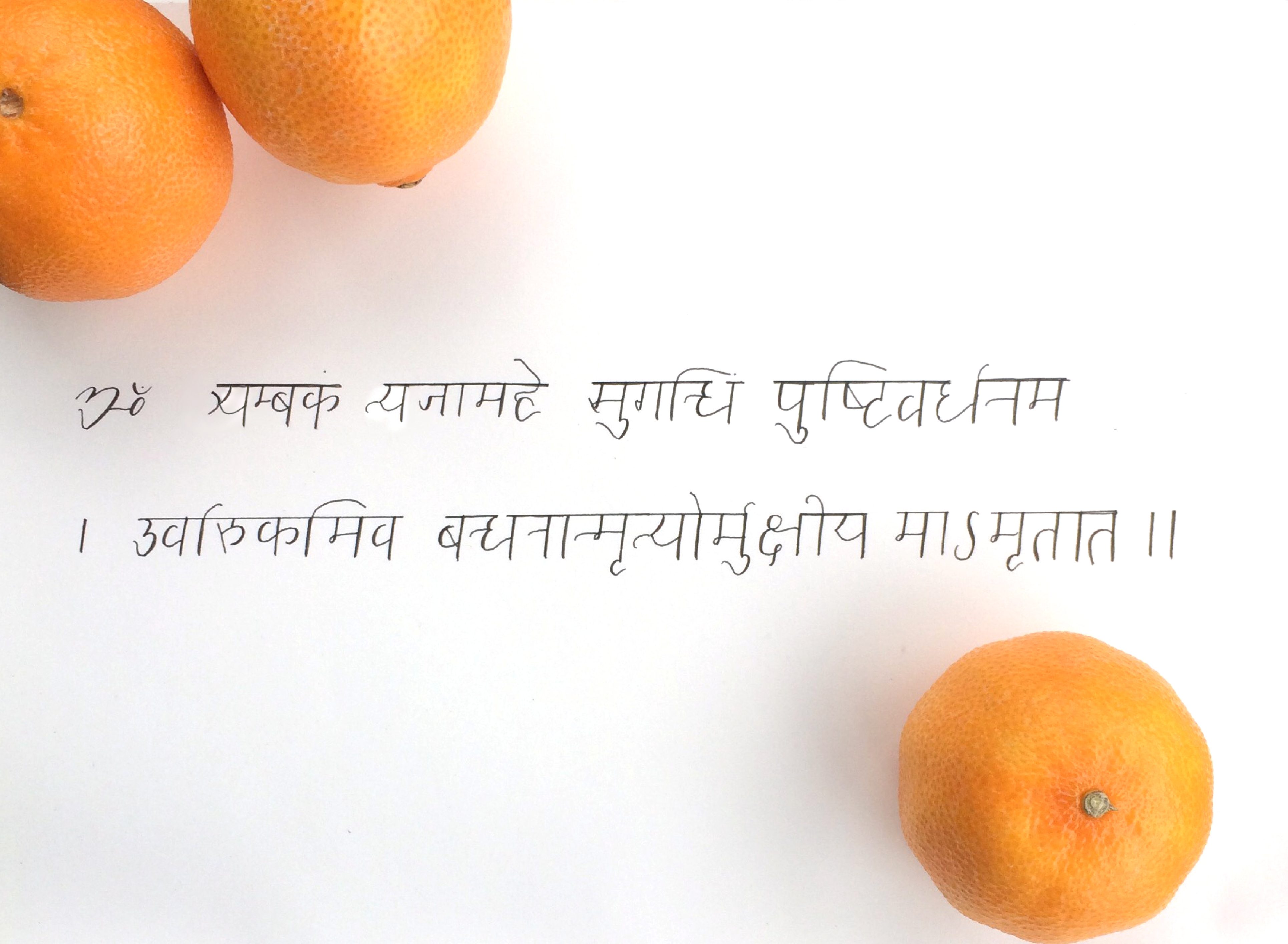

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali sheds light on how to attain an efficient and effective art of practice. The sutras (literally “threads”) are short statements, each containing a complex meaning. One such sutra gives a formula for the art of perfect practice: Abyāsavairagyābyhām Tannirodhah, “The ultimate goal of yoga is accomplished through the alternation between intense practice or abhyāsa and its opposite state, vairāgya, or rest and detachment from that practice.”

Abyhāsa or “practice” is the act of strongly cultivating focus toward a desired goal, idea or action, from practicing the cello to learning how to ski. In this state, attention is directed towards a particular area of study to develop a deeper level of understanding and expertise.

Vairāgya, or detachment from practice, on the other hand, allows attention to be free from the object of focus and practice. This required state of rest allows what is studied to naturally develop and integrate within the body and mind. Just as practice enhances a skill, rest allows that skill to cultivate deep within the body and mind. This simple, yet profound approach mimics the cyclical rhythm of nature, ever-evolving and always moving towards a state of perfection and balance.

As a confirmed “Type A” personality, this was far from my usual approach. As I began to incorporate the idea of sādhanā into my life, I now spend less time in practice, and more time noticing the benefits that accrue from it. Finally, the act of practice is no longer an obligatory effort and more of a meditation.

Jim Kulackoski holds an adjunct faculty position at Loyola University Chicago and runs Darshan Center, where he leads and develops programs such as teacher trainings, workshops and a healing clinic.

No Responses to “Practice—and rest—make perfect”